Trusts are widely used for estate planning, asset protection, and long-term wealth transfer, but they are often misunderstood from a tax perspective. One of the most important and costly differences between trusts and individuals lies in how income is taxed. Unlike personal income tax brackets, which are spread over a wide range of income levels, trusts are subject to compressed tax brackets that reach the highest federal rates very quickly. Without careful planning, this can result in significantly higher taxes and unnecessary erosion of family wealth.

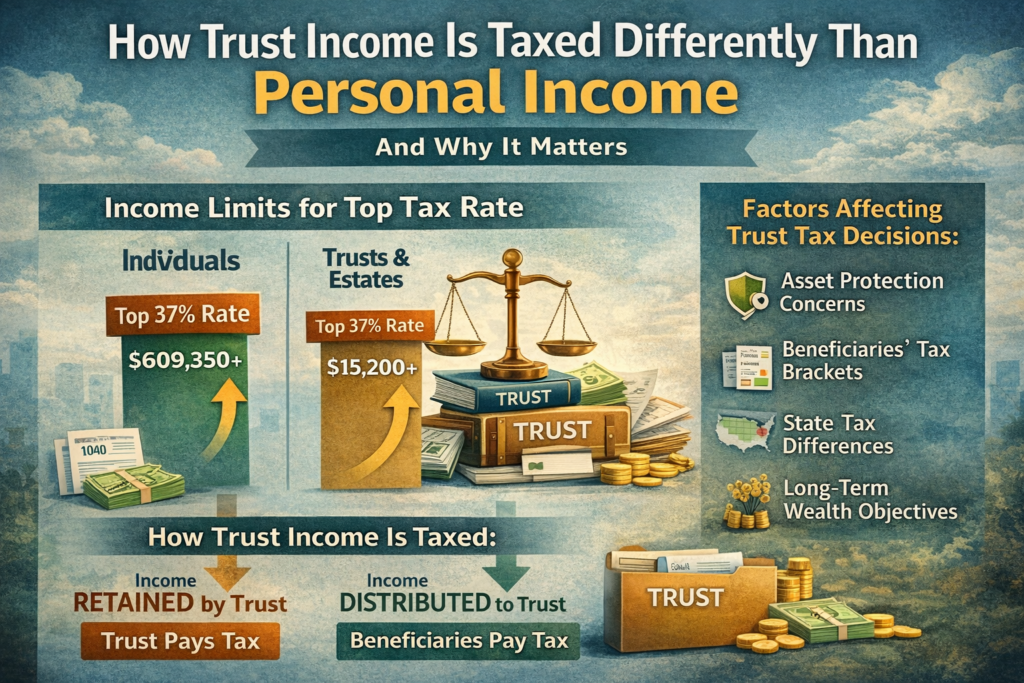

For individuals, it takes a substantial amount of income to reach the top federal marginal tax rate. Trusts, however, reach the highest rate of 37% at just over fifteen thousand dollars of taxable income, an amount that is indexed annually but remains relatively low. On top of this, trusts are also subject to the 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax at similarly low thresholds. As a result, a trust earning interest, dividends, or capital gains can face an effective federal tax rate exceeding forty percent far sooner than an individual taxpayer would.

The key factor that determines how trust income is taxed is whether the income is retained by the trust or distributed to beneficiaries. When income is retained, the trust itself pays the tax and the compressed tax brackets apply. This structure can be particularly punitive for trusts that hold investment portfolios or income-producing real estate. In contrast, when income is distributed, the trust typically receives a distribution deduction and the income flows through to beneficiaries, who report it on their personal tax returns. In many cases, this shifts income from a high-tax environment to one with significantly lower marginal rates.

While distributing income often produces tax savings, the decision is not purely mathematical. Trusts are created to serve specific legal and family objectives, and tax efficiency must be balanced against those goals. Trustees may need to consider asset protection, creditor exposure, divorce risk, or a beneficiary’s ability to responsibly manage money. In some situations, retaining income within the trust despite higher taxes supports the broader purpose of preserving and protecting wealth over time.

There are also circumstances where keeping income in the trust makes strategic sense. Asset protection concerns are a common reason, particularly when beneficiaries are in professions with higher litigation risk or are experiencing marital instability. Trusts designed with spendthrift provisions may intentionally limit distributions to prevent rapid dissipation of assets. Additionally, in certain cases, the state tax treatment of trusts may be more favorable than the beneficiary’s state of residence, making trust-level taxation comparatively efficient despite higher federal rates.

On the other hand, distributing income is often advantageous when beneficiaries are in lower tax brackets or reside in states with low or no income tax. This is especially true for trusts that generate ordinary income such as interest, dividends, or short-term capital gains. Shifting income to beneficiaries can significantly reduce the combined tax burden paid by the family as a whole, allowing more wealth to remain invested or available for long-term planning goals.

Capital gains present a unique challenge in trust taxation. In many cases, capital gains are taxed at the trust level even when cash is distributed to beneficiaries. Whether gains can be passed through depends on the trust document and applicable state law. Well-drafted trusts often include provisions that allow capital gains to be treated as distributable income when appropriate, creating flexibility to manage taxes more efficiently. This highlights the importance of proper trust drafting and ongoing coordination between trustees, attorneys, and tax advisors.

The impact of these rules is often underestimated. Without annual planning, trusts can quietly lose a substantial portion of their income to taxes year after year. Over time, this drag can materially reduce the value of the trust and the benefits ultimately received by beneficiaries. By contrast, thoughtful distribution planning can lower overall taxes, preserve trust objectives, and extend the life of family wealth across generations.

Trusts are not taxed like individuals, and that distinction matters far more than most people realize. Compressed tax brackets make it essential to evaluate trust income each year and determine, intentionally, where that income should be taxed. The right approach depends on tax rates, trust terms, beneficiary circumstances, and long-term family goals. When trust administration and tax planning work together, families are better positioned to protect assets, minimize taxes, and ensure that trusts fulfill their intended purpose.